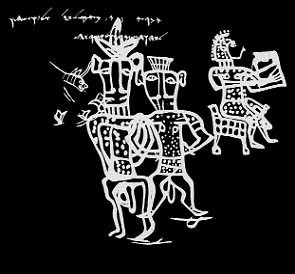

This week's portion of the week is Bo (Come!), which together with the latter part of last week's portion (Va'era) combined to form the heart of the Passover story. The 10 plagues overlap both portions. To my eye, the first ten chapters of the book of Shmot (Exodus) come across as a a narrative description of a panel of pictograms on some pyramid wall. The khartoomim (Pharaoh's Royal wizards), staffs morphing into snakes, the centrality of the river, and the litany of plagues have a very Egyptian flavor.

Documentary analysis of the plagues suggests that not the 10 plagues didn't originate from one source (Moshe for the devout). Rather, the Priestly school (P) was responsible for some them while a later combination of the Yahwist and Elohists schools (JE) were the origin of the rest. In any case, I'd like to turn the discussion over to Littlefoxling's comments on Ve-era & Bo ; I highly recommend reading the comments as well.

Today in the life of the Jews....The Capitulation of Pernambuco in 1654; In wake of the inquisition, many Jews fled to Latin America, whose rapidly developing cities would swarm with Marranos. Since Pernambuco (now known as Recife) was one of Brazil’s major port cities, it isn't surprising that a significant Jewish community developed here too (the tzniusdik ways of the Pernambucanas were another good reason to dock there).

Today in the life of the Jews....The Capitulation of Pernambuco in 1654; In wake of the inquisition, many Jews fled to Latin America, whose rapidly developing cities would swarm with Marranos. Since Pernambuco (now known as Recife) was one of Brazil’s major port cities, it isn't surprising that a significant Jewish community developed here too (the tzniusdik ways of the Pernambucanas were another good reason to dock there). The Dutch seizure of Pernambuco from the Portuguese was strongly supported by the Jews, and in the tug-of-war between the two colonial powers, the Jews fought alongside the Dutch. Eventually, the Portuguese reconquest of Pernambuco resulted in a mass exodus of the city’s Jews to Amsterdam and ultimately to New Amsterdam, which was destined to become the greatest city of refuge in history.